Library Research Project:

The San Francisco Public Library

Melissa Woods

San Jose State University

LIBR280_12

13 May 2013

Professor Beth Wrenn-Estes

California’s Public Library Efforts

San Francisco – Queen of the Pacific

The Meeting

|

| Current Library Logo |

The

San Francisco

public library’s history is one of rocky beginnings. Established in 1878, the library was born out

an early literary culture, enormous wealth at a time when the free public

library was increasingly popular. What

is interesting is how one can trace the history of the public library movement

in America using the

evolution of San Francisco’s

own library system. We can see how the

public library got its start, but also how the movement evolved through the

early twentieth century by analyzing the library’s establishment, its staff,

and even the buildings that housed the collections. We can see an evolution from the librarian as

the custodian to the librarian as a community educator and advocate. And we can also see how the library started

as a tool for education and also a tool of suppression. San

Francisco’s library offers a slice of American history

that shows what it took to begin the public library movement and what it takes

to keep it moving.

The Free Public Library Movement

|

| Salisbury, Connecticut |

The first free

public library was built in Salisbury, Connecticut in 1810, but it wasn’t until the Boston

Public Library opened in 1854 that the idea of a tax-supported public library

became an incredibly influential in the America (Wiley, 1996). Two major players in the founding of the

Boston Public Library wrote a report which would become, according to Wiley

(1996), “the Magna Carta of the public library movement, setting the tone for

American public libraries for the next half century or more.” The report argued that while there were many private

libraries at the time, those libraries were inaccessible to the masses and

therefore did not serve the needs of the public (Wiley, 1996). It also added that public libraries would be

a supplement to public education systems that only taught up to a certain point

and then offered no access to further education (Wiley, 1996). And so, in areas where there were enough

community resources, dense population, civic pride, and the desire to conserve

the historical record, the idea of the free public library spread (Garrison,

1979). While this is part of the story,

it fails to recognize that there were other, less altruistic reasons that the public

library became popular. For instance,

around the time that the public library movement idea was spreading, there was

a period of labor unrest and mass discontent which put the ruling white,

upper-class, male gentry on a shaky ground (Garrison, 1979). The public library became a way to respond to

the issue by equalizing education rights and reducing lower-class alienation

(Garrison, 1979). Furthermore, Garrison

(1979) argues that the public library was also a way for the ruling body to

practice social control as they were the governing body of library purchasing

and sometimes censorship (Garrison, 1979).

So while the argument of the education of the masses was solid, it may

have appealed to the ruling class for several reasons. Regardless, the idea spread throughout the Americas and

eventually found its way to the West.

California’s Public Library Efforts

California was swept up by the public

library movement though the idea proved quite difficult to implement. This was because the legislation needed to

generate funds for the library was difficult to promote (Held, 1973). As early as the 1850s, there was evidence

that California

cities supported the idea of legislation that would create a tax to fund a free

public library. But, it would not be

until the 1870s that attempts at legislation would begin in earnest (Held,

1963). Cities like Sacramento

and San Jose made legislative attempts, but San Francisco and Los

Angeles were the only two cities that were successful

in creating legislation that would directly

result in the rise of a city library

(Held, 1963).

|

| CA Golf Rush Relief Map |

San Francisco – The Queen of the Pacific

Nineteenth

century San Francisco

was a time of great change. The city

evolved from a sleepy town to a boom town, and eventually a major city, in

almost the blink of an eye. And the

credit of this mass migration to the West is given to one thing; gold. Though the San

Francisco Bay had been

explored as early as 1769, it wasn’t until 1835 that the town of Yerba Buena was born (“San Francisco,” n.d.). That was when an English pioneer named

Capitan William Andrew Richardson set up the first dwelling, a tent made from

four planks of redwood and a ship sail (“San Francisco,” n.d.). At the time that Richardson

built his tent, the US did

not yet own the area and wouldn’t for another eleven years (“San Francisco,” n.d.). But after eleven years of fighting over the

territory, the US Marines declared the area the property of the United States and named it San

Francisco (“San Francisco,”

n.d.). The settlement was slow growing

in its early years. In fact, the

permanent population did not exceed more than 50 people until 1844 (“San Francisco,” n.d.). In 1848, just before the discovery of gold on

the American River, the town had grown to about 200

homes which were inhabited by about 800 settlers (Bacon, 2002).

When James Wilson

Marshall discovered gold from the American

River at the site of

John Sutter’s

sawmill an international frenzy was sparked and thousands flocked to the area

in search of riches (“California,”

n.d.). By August of 1848, the population

had grown to include 4,000 gold miners and by 1849 San Francisco boasted a population of 25,000. (“California,”

n.d.; Bacon, 2002). At the time, San Francisco’s culture

was one of diversity with elements of both opulence and seedy behavior. Miners and sailors would spend their time in

gambling dens or brothels and in some cases would pay top dollar just to have a

woman at his side (Bacon, 2002). But

those that truly struck it rich, often by establishing businesses related to

mining, were becoming civic leaders and building opulent mansions along the

city’s hills (Bacon, 2002). San Francisco was also

extremely literary for the time. By the

middle of the 1850s, the city had a well-developed book trade and more

newspapers, in more languages, than major metropolitan cities such as London (Wiley, 1996). And, according to Wiley (1996), “there were more

college graduates in early San

Francisco, some said, than in any other American

city.”

|

| Broadside from the Gold Rush |

|

| Military Ball in S.F. - 1863 |

In the 1860s there

was a second wave of immigration into San

Francisco which brought both sophistication and racial

tension (Wiley, 1996). Called the ‘Queen

of the Pacific,’ by the end of the 19th century, there were palatial mansions, the

largest luxury hotel in America

at the time, the Palace Hotel on Market

Street, and a very opulent city hall (Wiley, 1996). But with the end of the Civil War, the city

was going through an economic downturn (“California,”

n.d.). This spurred labor unrest and a

general distrust in Chinese laborers leading to the Chinese Exclusion Act of

1882 which barred Chinese immigration until 1902 (“California,” n.d.). It was amidst this tumultuous time that the

city decided it was time for a free public library.

|

| Chinese Miners |

The

origins of the San Francisco Public Library can be traced to a meeting that was

held by concerned citizens of the city in the summer of 1877 (San Francisco

Public Library, 2013). California’s

senator, Senator Rogers, became the chief spokesman for those that were behind

the library campaign and he has been credited with personally collecting data

about libraries in the US

and overseas and he circulated that data around San Francisco in an effort to drum up support

for the campaign (Held, 1973). The

meeting was held at Dashaway Hall on Post

Street in San

Francisco and with the hopes of sharing the data that

had been collected and establishing a need for a public library (Wiley, 1996). Rogers

placed Judge E. D. Sawyer in charge of the meeting and it was well attended

(Wiley, 1996). Among those present, two

of the more prominent figures in the history of the library was Andrew S.

Hallidie and Henry George (Held, 1973).

Hallidie, who is better known as the inventor of the cable car, was the

head librarian of the Mechanics’ Institute Library in the city and he continued

to be an advocate for the free public library throughout his life (Wiley, 1996). Mr. George, another staunch advocate of the

free library movement gave a report of information about libraries in the US and Europe

at the meeting (Held, 1973). The report

stated that: “(1) People were willing to support public libraries with taxes.

(2) A public library was not able to exist on subscriptions and donations. (3)

A public library led to an increase in reading on the part of the public. (4)

The average cost per volume of a good library was $1.25. (5) Libraries were

often augmented by donations of private collections” (Held, 1973). The culmination of the meeting was a

resolution and proposed legislature (called the Rogers Act) that would later be

passed and signed by Senator Rogers on March 18, 1878. The legislature authorized “any incorporated

city or town to levy a tax not exceeding one mill (one-tenth of one cent) on

the dollar of assessed property” (Held, 1973).

The fact that the legislature included all of California was extremely significant as it

solved the issue that several cities had of being unable to pass their own

legislature (Held, 1973). The other

interesting fact about the legislature was that it called for the San Francisco

Library to be governed by a

self-perpetuating board of trustees that would supposedly keep the library from

“the general corruption of city politics” (Wiley, 1996).

|

| Dashaway Hall |

| |

| Political Cartoon (Kearney not pictured) |

By

analyzing the meeting, we can begin to understand the nuances of the free

public library that Garrison suggested. The

call for a public library came at an extremely tumultuous time in San Francisco’s history. The completion of the transcontinental

railroad in 1869 coupled with a depression that struck Eastern States in 1873

created a large influx of population of unemployed men and women in the West

(Wiley, 1996). Even worse, between the

years of 1870-1875, an estimated 80,000 Chinese immigrants arrived in the area

(Wiley, 1996). Needless to say, there

was a large amount of men and women who competing for work which brought about

the ‘terrible seventies’ in San

Francisco (Wiley, 1996). Labor unrest was triggered by people who were

resentful of the economic overlords and disappointed by crushed dreams of easy

riches (Wiley, 1996). And much of this

unrest, unfortunately, was targeted toward Chinese immigrants. In fact, the same year that San Franciscans voted

to establish the San Francisco Public Library, there was a major riot in the

city where a group of protesters broke off and ran towards the docks attacking

Chinese people and Chinese-owned shops along the way (Wiley, 1996). At the meeting, there were arguments made suggesting

that the library would be about educating the masses while also controlling

some of the labor unrest. Dr. George

Hewston suggested that a public library would “be open to all classes, but

principally frequented by the poor; that the man in corduroy is treated with

the same courtesy as the rich man in broadcloth…and that charm of the place is

its perfect freedom” (Wiley, 1996). But

in the same speech, he remarked that the library would “do more to overcome

hoodlumism than the extremest rigors of the law” suggesting that, yes, the

library would be good for the masses, but at the same time, it will also help

reduce some of the labor unrest. Another

attendee, Denis Kearney, a rioter who was the head of the President

Workingmen’s Party, remarked that “one educated man is worth a whole Committee

of Safety and not nearly as liable to shoot his neighbor” (Wiley, 1996). So while it is not said outright, we can see

that many were in agreement that a great way to solve the labor unrest and

possibly turn the population’s anger away from the ruling party would be to

construct a public library. This is

further evidenced by the fact that the founders were all part of the white,

upper-class, male gentry of the city.

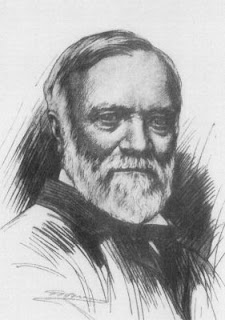

The

board of trustees that was established to run the San Francisco Public Library

was made up of eleven men. They were

George H. Rogers, John S. Hager, Irving M. Scott, Robert J. Tobin, E.D. Sawyer,

John H. Wise, Andrew J. Moulder, Louis Sloss, A.S. Hallidie, C.C. Terrill, and

Henry George (Held, 1973). The board had

many things in common. Firstly, they

were all white, highly educated male members of San Francisco. Many of them were lawyers, judges, and State

Senators or even all three, like E. D. Sawyer.

A transplant from New Orleans,

Sawyer started his career as a lawyer who dealt mainly in mining disputes

(Shuck, 1901). In 1853, at the Whig

convention, he was nominated and elected as a democratic State Senator (Shuck,

1901). After his retirement from politics,

Sawyer moved back to San Francisco

and became a judge, served as an educational director, and became a prominent

member of society (Shuck, 1901). The

trustees were civic minded and were often involved in California politics like John S. Hager. Hager, originally from New Jersey, was a delegate at the first and

second California Constitutional Conventions, though he was not officially

listed in the first (Vasar & Meyers, 2013).

As one can see, many of the trustees were not originally from San Francisco. Like the

majority of the city, they moved after

news of the Gold Rush and they profited from mining or from working with

miners. Take Irving M. Scott. He was an engineer and draughtsman who worked

for the Union Iron Works creating machinery that would make mining more

efficient (New York

Public Library, 2013). While this was

his main career, he is best known as the head of the project which built the

battleship Oregon, the first battleship ever built on the

Pacific Coast (New York Public Library, 2013). Some members, like

Robert J. Tobin were

involved in several social and civic organizations. According to his obituary written in the San Francisco Call (1906), Tobin was a

judge, a police commissioner, a charter member of the Society of Pioneers, and

one of the Incorporators of the Hibernia Bank which started in 1859. Lastly, the trustees were literary men. Some, like A.S. Hallidie, were already

working in libraries and at least one of the members, Henry George, was a

newspaper man. George moved from Pennsylvania with his

family and got a job as a

typesetter (Henry George Historical Society,

2009). After the death of Abraham

Lincoln, he wrote several editorials which got him noticed, and he eventually

got a job at the Times (Henry George

Historical Society, 2009). Within a short period of time, George was

the managing editor for the newspaper (Henry George Historical Society, 2009). These men were extremely committed to a free

public library but not every powerful member of San Francisco was like minded and as a

result, the main library had very rocky beginnings.

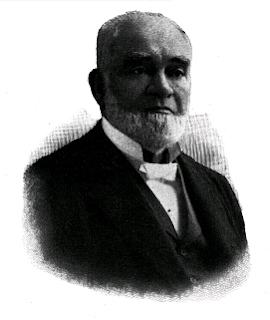

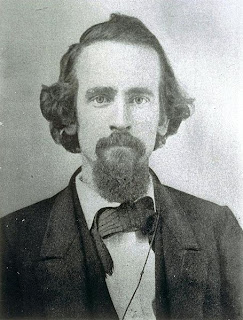

|

| E.D. Sawyer |

|

| John Hager |

|

| Irving M. Scott |

|

| Henry George |

Despite

the city’s enormous wealth, there was little support in San

Francisco and in the US in general for government

funding of public institutions. “It was

an era across the nation when private enterprise prevailed, and little

attention beyond the funding of public schools was given to investment in

public institutions” (Wiley, 1996). This

mentality created financial difficulties at the onset of creation of the

library. After the Rogers Act passed in

1878, the trustees requested that a tax by levied of 3/10 of a mill and an

appropriation of $75,000 be given to the library to begin operations and to

start the purchasing of the library’s collection (Held, 1973). San

Francisco city officials disagreed with the amount and

the library was given an appropriation of $24,000 instead (Held, 1973). The trustees deemed the sum inadequate but

opened anyway, deciding to donate some of their own resources until the end of

that fiscal year hoping that San

Francisco’s Board of Supervisors would raise the

appropriation after the library had already opened and shown it was successful

(Held, 1973).

Between

the library’s opening in 1878 and 1906 the main branch moved locations three

times. This was a period that was marked

by continued financial struggles and high staff turnover rates. But the library was instantly successful with

its users as we can see from the library’s records. If we look at card membership statistics during

this time, we see the library’s steady growth.

In 1890, there were 10,354 library card memberships active (San Francisco Board of

Supervisors, 1895). After a small

downturn, membership grew steadily so that in 1895 membership had grown to

16,411 (San Francisco

Board of Supervisors, 1895).

Library cards were

issued for two year periods and, until 1901, only one book could be checkout

out at a time (San Francisco Public Library, 1900). After 1901, a time of great change in the

library field, you could apply for a special card which would allow the holder

to borrow more than one (San Francisco Public Library, 1900). And in 1902, the library began stamping their

books with the date they were due rather than the date that the book was

checked-out (San Francisco Public Library, 1900).

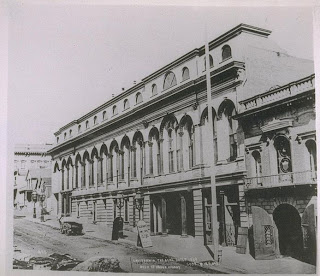

|

| Pacific Hall |

Public libraries

in California

were usually located in one of two places.

First, as the city government was considered a patron of the public

library, often a space would be provided in the city hall (Held, 1973). However, these free spaces were often

inadequate for the needs of the library and they were often forced to use what

little budget they had to rent a space large enough to accommodate their needs

(Held, 1973). San Francisco’s public library was no

different.

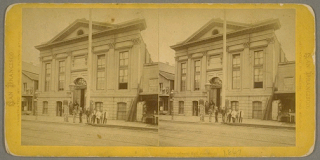

In 1879, before

the library had received any money from the state, a room was rented on the

second floor of Pacific Hall on Bush and Dupont (later renamed Kearny) Streets (Wiley, 1996; San Francisco

Public Library, 2013). They removed a

stage that was in the room, laid fresh oilcloth, touched up the fresco’s that

were in the room, and constructed a small office in what would be the reading

room (Wiley, 1996). Shelving was built

and 5,000 books, which were borrowed, donated, or bought on credit, were put on

the shelves. A newspaper reading area

was added in the main gallery and lastly, a wire screen was installed in front

of the bookshelves to assure only employees could have access to them (Wiley,

1996). At the establishment of the

library, there were so few books that the library did not grant borrowing privileges

and would not for several years (Wiley, 1996). The library opened with a

ceremony held on the evening of June 7, 1879 (Wiley, 1996).

Even though there

were no borrowing privileges, the library was an instant success. It was reported that in the twenty-one days

after the formal opening, 18,000 people visited the library (G. Bosc, 1968). Because of the library’s success, the budget

was immediately doubled and they increased the volumes in the collection to

30,000 (G. Bosc, 1968). Within ten

years, the library had outgrown Pacific Hall and begun looking for a new,

larger, space. Joy Lichtenstein, a

library employee since 1886 described the library the following way:

|

| Pacific Hall |

When I entered the

employment of the library it was on Bush

Street, on the north side above Kearny…The library was up one flight of

stairs. As you entered a long hall there

was seated at the entrance an old man, in fact there were two of them –

combined janitors and doorkeepers. The

one in attendance would hand you a brass tag, fairly large, which you carried

in with you and which you absolutely had to deliver before you could

leave. The library itself was in back of

a tall wire screen and there were no books which the public could touch except

by making out applications. The wooden

bookstacks rose to the ceiling, and the boys scrambled around by means of

sliding ladders which resembled those used in shoe stores. The books had class and shelf numbers but the

Decimal System was still far in the future.

The catalogs were printed and very much out of date. The public secured books…with a pink or white

oblong slip…there were handed through openings in the fenced off portion and

three ladies were always in attendance.

They were ladies who had secured their positions by means of influence

not political. They were not bookish and

of course the boys were not; so it was a sort of hit or miss proposition for a

member of the public to procure a desired book - California Library Bulletin, June 1950 (Wiley,

1996).

In 1889, the

library moved to the Larkin Street

wing of City Hall though at the time there were already discussions underway to

build a separate building for the main library (G. Bosc, 1968). As these discussions took several decades,

the library was strapped for space again and in 1894 it moved to the third

floor of the McAllister Street

wing of City Hall (G. Bosc, 1968). It

remained at this site until the earthquake and fire of 1906 (Wiley, 1996). Interestingly, in 1903 the library was able

to purchase land which was intended for a new main library (Wiley, 1996). But the real estate would be disputed for

many years, and the library would not move into a separate building until 1915

(Wiley, 1996). Until then, the library

was renting space to house its main collections.

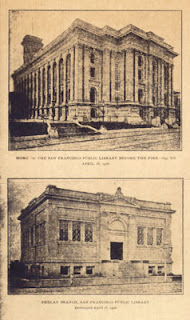

|

| Main Branch (top) and Branch (bottom) |

Some interesting

services that were started in the library between 1878 and 1906 were a

periodical room started in January of 1895 and a Juvenile department which

began in October of the same year (G. Bosc, 1968). The Juvenile department replaced what was the

‘ladies reading room,’ in 1897, which moved from its original space on the

second floor of the building, to the ground floor (Wiley, 1996). The ladies reading room, according to the San Francisco Call, had tables where the

women could sit and on the tables were travel books and other literature that

would “take from them the desire for trashy literature” (Wiley, 1996).

The

first librarian ever hired was Albert Hart (Wiley, 1996). He was hired in 1879 with the understanding

that he would not be paid until the library could secure funding (Wiley, 1996). Opening a library without pay and without

funding took a toll on Hart and within the first fiscal year he resigned

(Wiley, 1996). He was replaced by

Charles Robinson who also resigned after seven months, claiming overwork

(Wiley, 1996). In 1880, with enough

books to finally become a circulating library, the trustees hired Frederic

Beecher Perkins (Wiley, 1996). Perkins

was a member of the Beecher

family and he was cousin to the famous author Harriet Beecher Stowe who wrote Uncle Tom’s Cabin (Wiley, 1996). He was known for his rigidity and was even

quoted as saying “a library is not for a nursery; a lunch-room; a bed-room; a

place for meeting a girl in a corner and talking to her; a conversation-room of

any kind; a free dispensary of stationery, envelopes and letter-writing; a free

range for loiterers; a campaigning field for mendicants, or for displaying advertisements;

a haunt for loafers and criminals” (Wiley, 1996). Though rigid, he was also inventive. Perkins claimed at least two innovations for

the public library while employed at the library. First, he advocated painting the call numbers

directly on books rather than using paper labels (Held, 1973). He also developed a numbering system for

patrons that involved a revolving rack for request cards presented at the desk

(Held, 1973). This allowed for a strict

enforcement of the ‘first come first served’ principle (Held, 1973). Unfortunately, Perkins’ rigidity got the

better of him and he resigned after being fined for ‘manhandling’ an unruly

child in 1887 (Wiley, 1996).

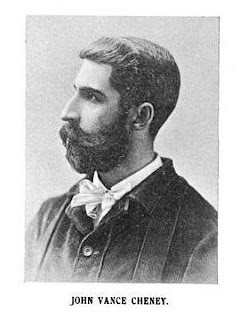

John Vance Cheney,

was hired after Perkins left (L. Bosc, 1968). Cheney, who was a poet, essayist,

and librarian, was born and educated in New

York (“Cheney, John Vance,” n.d.). After moving to San Francisco, he was a postal clerk briefly

before assuming the position at the library (“Cheney, John Vance,” n.d.). While he was librarian, he oversaw the opening

of the first two library branches and hosted an American Library Association

Conference in 1891 (“Cheney, John Vance,” n.d.). After Cheney resigned in 1894, George Thomas

Clark and was hired (Wiley, 1996). Clark

and his assistant Joy Lichtenstein left the library shortly after the

earthquake in 1906 (Wiley, 1996).

According to Lichtenstein, “Clark had

been a difficult man, remote and taciturn – ‘not a man of very attractive

personality’” (Wiley, 1996). He was head

of the library for twelve years and in that time the library grew to be the

eighth largest library in the United

States (Wiley, 1996). Clark left in 1906 to become the head

librarian of Stanford

University (Wiley, 1996).

Little

is known about the assistants of the library from its beginning to the 1906 earthquake

though there were some prominent library assistants working during this

period. For instance, Joy Lichtenstein, a

rare San Francisco native, started working at the San Francisco Public library

in 1886 (Cutter, 1904). He was an author

and also served as president of the California Library Association in 1904

(Cutter, 1904).

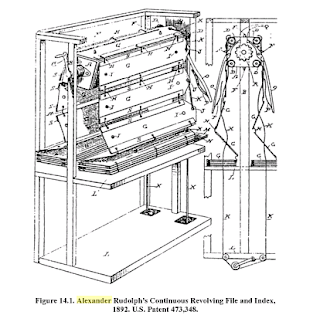

There

was also Alexander Rudolph who was a library assistant in the 1890s (Buckland,

2006). He was the inventor of the

Rupolph Continuous Index (G. Bosc, 1968).

This was an automatic cataloging machine that was designed to hold up to

12,000 catalog entry cards in an endless chain (Davis & Wiegand 1994). The cards were held on pressboard sheets

which would display 175 at a time and were rotated beneath a glass plate at the

top of the machine when a user turned the handle (Davis & Wiegand

1994). While used for catalogs in areas,

such as Russia,

until the 1930s, it was generally unsuccessful (G. Bosc, 1968). This was due to the lack of capacity,

flexibility, and limited access compared to the card catalog (Davis & Wiegand

1994). While both of the above examples

were male library assistants, many of the library assistants were women. For instance, in the 1894-5 municipal report

for San Francisco,

all five of the library assistants were women (San Francisco Board of

Supervisors, 1895).

As far as the

salaries for the employees, it is difficult to tell from the municipal reports

what the average salary of a librarian was in San Francisco between 1878 and 1906. We can see that that the library did not

focus most of its spending on its staff in the early years. In fact, as stated earlier, the first

librarian did not even get paid, initially.

In the second fiscal year that the library was open, 1879-80, only $7,841.70

of the $38,615.04 that was spent was allocated to staff salaries (San Francisco

Board of Supervisors, 1879-80). There

was no indication of how the money was split amongst employees. In the fiscal year of 1894-5, the total that

was spent on salaries was $22,265.35 with roughly $1,500 being spent in the branches

and the remainder at the main library (San Francisco Board of Supervisors, 1895). At this time there were four branches and the

main building, with a total of thirty-eight employees (G. Bosc, 1968). Though

it is difficult to tell from the municipal reports, we do now that in 1894 the

library’s employees were being paid $48.95/month less than the average city

worker in San Francisco

and they worked longer hours.

Andrew Carnegie – Dirty Money?

|

| Andrew Carnegie |

While discussions

were underway to establish a separate main library, in 1901, the library was

offered a Carnegie grant for library buildings which totaled $750,000 (G. Bosc,

1968). The trustees secured a commitment

to spend the money on a new main library as well as opening new branches. But the proposal to accept the money did not

go smoothly. The San Francisco Labor

Council quickly opposed accepting the Carnegie grant because the gift was

considered a “presumptuous claim of a wealthy nonresident to dictate our

municipal policy in the assumed name of philanthropy” (Wiley, 1996). Additionally, the money was thought, by the

Labor Council, to be acquired by questionable means through the sale of war

goods to the United States

at “extortionate rates” (Wiley, 1996). A

library constructed with Carnegie money, the Labor Council concluded, would

‘stand as a perpetual charge against the morals of the community’ (Wiley,

1996). Despite the staunch objection by

the Labor Council, San Francisco’s

Board of Supervisors voted to accept the grant.

They also put a $1.647 million bond measure on the ballot in 1903 to

match the Carnegie grant and to provide funds for the new main library (Wiley,

1996). Though nothing would be settled

until years later, it was in 1901 that the discussions for a new main library,

and indeed a new Civic

Center would begin in

earnest (Wiley, 1996).

| 1893 Colombian Exhibition in Chicago |

At the turn of the

twentieth century, the City Beautiful movement was sweeping the nation. The City Beautiful movement began with White City

and architect Daniel Burnham at the 1893 World Colombian Exhibition in Chicago

(Casey, 2012). A response to failing

urban life, the hope was that beautification of the city would improve social

issues and inspire civic loyalty (Casey 2012).

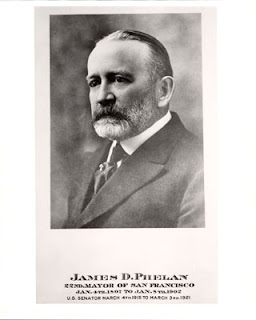

San Francisco’s

move to improve itself took the form of former Mayor and library advocate James

Phelan. He invited Burnham, the father

of the City Beautiful movement, to San

Francisco in 1904 and persuaded him to draw up new

plans for the entire city (Casey, 2012).

Burnham complied. Part of these

plans included a new Civic Center that would be the center of the city and would

include features such as an extension to Golden Gate

Park,

called the panhandle (Wiley, 1996). The

plan included a new library, but the location was hotly contested. Phelan wanted it to be across from the

panhandle bounded by Fell, Franklin,

Hayes, and Van Ness Streets, but the Board of Supervisors felt it should rest

at the south side of City Hall (Wiley, 1996).

Phelan ultimately won his battle and the new site for the main library

was approved in 1905 (Wiley, 1996). The

beautification of the city was never fully realized, however, due to the

infamous 1906 earthquake.

Earthquake and Fire

|

| Devastation of Earthquake with City Hall Background |

At 5:13am the

morning of April 18, 1906, a major earthquake raced in a southeasterly

direction at 7,000 miles per hour down the San Andreas Fault, severely damaging

San Francisco

(Wiley, 1996). The earthquake lasted

about 1:30 minutes, but because much of the city was built on landfill and it

was constructed poorly, many houses were destroyed (Wiley, 1996). Immediately after, several fires sprang up and

further decimated the city (Wiley, 1996).

Over 4½ square miles of the city was leveled, 250,000 lost their homes,

and around 3,000 people died as a result of the earthquake and fires (Wiley,

1996). The main library at City Hall

lost 138,000 books and newspapers because of the Ham and Eggs Fire, so called

because a woman, who was trying to cook her morning meal using a damaged

chimney, started the fire (Wiley, 1996).

At the time the earthquake hit, there were 15,000 books on loan; only

1,500 were returned (the last one was returned in 1981). And though the main library was destroyed,

there were four branches remaining and around 25,000 books left undamaged

(Wiley, 1996).

Between

the years of 1907 and 1920 the library grew immensely. For instance, in 1906 there were a total of

25,000 volumes in the collection with 25,702 circulated items (G. Bosc,

1968). There were four branches and

9,595 cardholders (G. Bosc, 1968). But

by 1917 the library had grown to 191,960 volumes with 1,183,754 circulated

items (Bosc, G., 1968). The library went

from four to seven branches (there had been eight in 1906) and there were

57,966 volumes (G. Bosc, 1968). It is

clear that the library was immensely popular and important to San Francisco citizens, but it was during

this time that the librarians and assistants were challenged with rebuilding

the library from the ground up while still working long and low-paid hours.

It

was also a time when the public library had been evolving and growing in the

number and type of services provided. The

evolution was mainly focused on promoting user services and we can see this

evolution with the San Francisco

library. For instance, extended services

like delivery services and deposit stations became a popular way to serve

library patrons (Held, 1978). In San Francisco, deposit

stations were small collections that were borrowed from the main library and

deposited in sparsely settled areas of the city, often in drugstores (Held,

1973). The manager of the station would

be paid around $15 per month to service it, and books could be requested of the

main library via regular mail (Held, 1973).

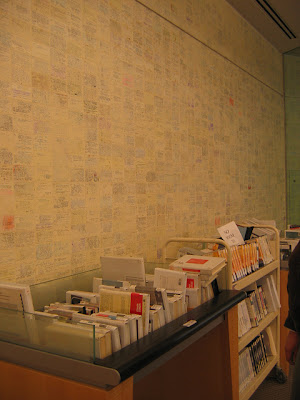

|

| Wall of catalog cards installed when the library moved to its current space in 1996 |

|

| Temporary Main Library after Earthquake |

Compared

to other city institutions, the library faired rather well after the earthquake

when it came to rebuilding. Firstly,

they had a small insurance claim that they were able to call upon and secondly,

the Library Fund still had $40,000 that they were able to use to rebuild

(Wiley, 1996). The main library was

still considered to be a part of the city’s Civic

Center but plans for the library and Civic Center

were slow to develop. The library

actually had to fight to begin rebuilding because the Board of Supervisors

wanted to use the same property for the new City Hall even though the library

had owned it since 1903 (L. Bosc, 1968).

Fortunately for the library, the President of the trustees filed an

injunction against the Department of Public Works which forced the Board of

Supervisors into conceding and looking for a new spot for City Hall (L. Bosc,

1968). In June of 1907, construction

began on a temporary main library that would stand until the final plans for

the city’s Civic Center was complete (Wiley, 1996) The building was at the corner of Hayes and

Franklin (Wiley, 1996). The following

fiscal year, the library received its first appropriation that was over the

legal minimum and planning began on a bond measure that would help to fund the

new main library (Wiley, 1996).

|

| Michael D. Young |

There

were efforts by Phelan to revive the original Civic Center

plans drawn up by Burnham prior to the earthquake, but a new sentiment was

growing in the city (Wiley, 1996).

Michael De Young, owner of the San

Francisco Chronicle, is credited as the voice of the effort to rebuild San Francisco with

business in mind; not beauty (Wiley, 1996).

But the plans for rebuilding the library, and the entire Civic Center

were slow moving and full of back and forth arguments. It wasn’t until the city was chosen as the

site for the official Panama-Pacific International Exhibition in 1911, that

there was a renewed sense of urgency in finishing the city’s Civic Center

(Wiley, 1996).

The

exhibition and a new mayor, James Rolph Jr., ushered in an era of development

which included the long awaited Civic

Center (Wiley,

1996). It was decided that the new Civic Center

would be built on the site of the old one since the city still owned the

property and after that decision was made, construction came quickly (Wiley,

1996). That is until a protestor

brought

up the Carnegie funds that were still on hold for the construction of a new

main library (Wiley, 1996). The plan was

to use some of the grant to fund construction of the new main library and the

remainder to build new branch libraries in the city (Wiley, 1996). The issue was hotly contested and ended up on

the November 1912 ballot (Wiley, 1996).

It passed and construction of the new Civic Center

continued. When it came time to draw up

plans for the library, the decision was made to trade the property that the

library owned for real estate that was closer and therefore better associated

with the new Civic

Center (Wiley,

1996). The official site of the new main

library was to be bounded by Larkin, McAllister, Hyde, and Fulton Streets

(Wiley, 1996). Now they just needed a

plan for the building itself.

|

| Hall of Machinery - Panama Pacific Exhibition |

|

| Preparing the ground for construction |

In 1913, the

library trustees arranged a competition to be judged by Phelan and two well

known architects; Cass Gilbert and Paul Philippe Cret (Wiley, 1996). Six local architects were chosen to enter,

and in 1914 the trustees announced George Kelham as the winner (San Francisco

Public Library, 2013). Kelham was

originally from Massachusetts and his first

job was at an architectural firm in New

York (Michelson, 2013). The firm sent him to San Francisco to supervise the rebuilding of

the Palace Hotel in 1906, and he remained once the project was complete

(Michelson, 2013). Aside from designing

the main library, Kelham was also the principal architect for the

Panama-Pacific International Exhibition and the principal architect for UC

Berkeley and UCLA (Michelson, 2013).

|

| Moving Books to the New Main Branch |

Kelham’s

design was a steel-framed granite structure that was designed to hold 500,000

books and have the capacity to expand to one million should the need arise

(Wiley, 1996). The exterior features

Roman arched windows set off by Ionic columns and though not part of the

original plan, five statues by Leo Lentelli were later added in the alcoves

between the columns (Wiley, 1996).

Patrons entered from Larkin

Street using three large, brass-framed doors that

led into a colonnaded vestibule (Wiley, 1996).

This led up to a broad staircase and the distribution room (Wiley, 1996). The vestibule, stairway, and delivery room

were all finished in travertine marble (Wiley, 1996). The delivery room, reference room, and the

main reading room all had painted beam ceilings and the doorways, bookcases,

and wooded fixtures were covered with an antique oak finish (Wiley, 1996). As one can see from the description, the

interior was designed to evoke an Italian Renaissance palazzo (Wiley,

1996).

|

| Front Doors of New Main Branch |

The

library finally sold enough bonds to begin construction and on April 15, 1915

ground was broken (Wiley, 1996). Almost

immediately, lack of funds halted construction and it was not until they

borrowed the excess funds from the San Francisco Municipal Railroad that they

were able to resume construction (Wiley, 1996).

On April 16, 1916, a cornerstone laying ceremony took place and on

February 15, 1917 the library was finally completed and dedicated (Wiley,

1996). The main library would remain

here until 1996 when they moved, for a final time, into a larger building next

door (Wiley, 1996). The building Kelham

designed now houses

the Asian

Art Museum though you can

still see evidence of the library in the museum such as the quote above the

staircase which reads “Books bear the messages of the wisest of mankind to all

the generations of men” (Wiley, 1996).

|

| Cornerstone Laying Ceremony 1916 |

The more

interesting developments in the library’s collection between 1906 and 1920, was

the 10,000 item music library that was purchased in 1911 from the Boston Music

Company and the rare books collection (Wiley, 1996). Both show a commitment to community groups, a

mentality that developed at the turn of the twentieth century in the library

field (Held, 1973). The music collection

purchase was arranged by Julius Rehn Weber who was a pianist and music teacher

in San Francisco

(Wiley, 1996). In 1920, at the

instigation of a library trustee named William Young, the library began to

systematically collect rare books and works of San Francisco’s fine printers (Wiley, 1996).

|

| Reading Room in the New Main |

|

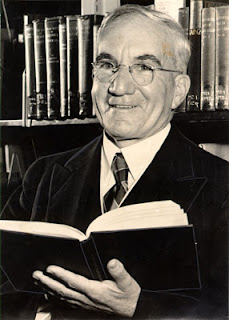

| Librarian Robert Rea |

William R.

Watson was hired as the city librarian after Clark

and his assistant Lichtenstein retired in 1906 (L. Bosc, 1968). He was the first trained professional

librarian to head the library (San Francisco Public Library, 2013). He was trained by Melvil Dewey (L. Bosc,

1968). He was also the head librarian

during a major milestone in library history.

During Watson’s service, the North

Beach branch bought a

collection of Italian language books and secured a spot as the first ever

library to cater to the needs of a minority group (Marco, 2012). Unfortunately, Watson was forced to retire in

1912 due to health reasons (Wiley, 1996).

He was succeeded by Robert Rea in 1913 (L. Bosc, 1968). Rea was a political appointee with no library

science training though he had worked at the library since the age of thirteen

(Wiley, 1996). He worked at the library

until 1945 and was a somewhat controversial because his career did not move

with the changing times. Rea grew up in

the library and it was the only job he ever had (Wiley, 1996). He presided over the construction of

seventeen new branches and, possibly his crowning career achievement, focused

and expanded the library’s collection (Wiley, 1996).

Unfortunately,

little has been said about the library assistants working during this era in

the library’s history. Library

assistants were no longer listed in municipal records or book bulletins and it

seems as though there is a lack of knowledge about the group in general. In the 1920s we get a better idea of the staff

culture though, unfortunately, it is not a positive one. For instance, in a letter to the Examiner written in 1920, a student

writes “It is about time the librarians…curb the chatter and patter of

lovenmeshed swains in their teens who come to use these places” (Wiley,

1996). Later in the 20s we learn that the

staff was mostly women and if a 1928 survey gives any clues, it would be safe

to assume the staff was not exemplary.

The board of trustees had requested an independent survey of the library

the resulting report was scathing, calling head librarian Robert Rea

“temperamentally unfitted for administrative

leadership” (Wiley, 1996). The remaining library staff faired no

better. The report found that the staff

was “almost entirely made up of women and that suffered from intellectual

inbreeding and lack of initiative because of the absence of encouragement for

the head librarian. There were also

serious shortcomings caused by the librarians’ lack of training, particularly

for librarians working with children” (Wiley, 1996). This shows that under Rea’s leadership,

though the library had substantially improved its collections, the focus on

training and professional leadership that the rest of the public library system

had promoted fell on deaf ears in San

Francisco.

|

| Staff working at the Main Library 1930s |

After the

earthquake, the library grew. But the

library was spending less than any other library in the western region and had

one-third the staff to boot (Wiley, 1996).

During this time, civic improvement clubs continually petitioned for new

branches and eventually voted to increase the library’s budget so that they

could meet their user’s demands (Wiley, 1996).

In the fiscal year of 1907-08 the library’s appropriation was $64,445

but by 1921-22 the amount had grown to $185,282 (Wiley, 1996). Even still, the librarians who worked in San Francisco worked 42

hour weeks and were paid between $85-95 a month, the lowest wage of any other

city employee (Wiley, 1996).

The history of the

San Francisco Public library shows a great example of the birth and growth of

the public library movement as well as the trials and tribulations that so many

had to go through to keep the library going.

While on the one hand, the public library movement was popular in a city

of highly educated, civic minded individuals, the library also started at a

time when labor unrest was at its highest suggesting that the ruling elite was

looking for a way to quell the unrest.

The library buildings also suggest that there was a level of distrust of

those

corduroy wearing poor men as it was designed, like many other libraries,

to reduce access to the collection.

Despite its instant popularity, the library continually had issues (as

so many do even today) finding the funding to support its users and its

staff. Throughout the library’s history,

it was the lowest paying city job with the longest hours. But the librarians and staff remained

dedicated and the library thrived. In

the rebuilding of the library after the 1906 earthquake, we see evidence of the

library field’s move to user access and community commitment that continues

today. Unfortunately, the library’s

history is also one that is lacking in a minority presence. In examining the history of the San Francisco

Public library, one is reminded of the trails that public libraries are facing

today. Despite beginning the library

without a penny and with few worthwhile books in its collection, San Francisco still

managed to pull off a widely successful and sustaining public library. Throughout the library’s history, there was

constant ebb and flow of funding, properly trained staff, and public

interest. But despite these trials, the

library still continues to be an important civic

institution with 28 branches

and a 6-floor main library which is valued highly among its users. Over the last decade or so, libraries have

faced difficult decisions with changing technologies and the economic downturn

in the United States. But if the public library movement and the

San Francisco Public library can teach current librarians anything, it is that

perseverance is the key. The library is

about education of the masses (altruistic or not) and it seems that patience

and persistence will lead to the continuation of the library in some fashion as

it has for over 125 years in San Francisco.

|

| Staircase in Main Library |

|

| Current Main Library Building since 1996 |

Bacon, D. (2002). Walking

San Francisco

on the barbary coast trail. San

Francisco:

Quicksilver Press.

Bosc, G. (1968). A

history of the San Francisco

public library: 1878-1917. (Thesis). San

Jose

State University,

San Jose.

Bosc, L. (1968). A

history of the San Francisco

public library: 1917-1968. (Thesis). San

Francisco

State University,

San Jose.

California.

(n.d.). In Encyclopædia Britannica Online

Academic Edition. Retrieved from

http://www.britannica.com.libaccess.sjlibrary.org/EBchecked/topic/89503/Califor

nia

Casey, C. (2012, July 6). Architecture spotlight: San Francisco civic center

[web log

post]. Retrieved from http://untappedcities.com/2012/07/06/architecture-spotlight-san-francisco-civic-center/

Cheney, John

Vance. (n.d.). in American Authors, 1600-1900 [serial online]. Retrieved

from Biography Reference Bank. (W.H. Wilson).

Cutter, C. (1904). State Library

Associations. The Library Journal, 29.

Retrieved from

https://play.google.com/store/books/details?id=lsjgAAAAMAAJ&rdid=book-lsjgAAAAMAAJ&rdot=1

Davis, D. & Wiegnad, A. (1994). Library Equipment. In Encyclopedia of Library

History.

Retrieved from: http://books.google.com/books/about/Encyclopedia_of_

Library_History.html?id=WR9bsvhc4XMC

Held, R. (1973). The

rise of the public library in California.

Chicago:

American Library

Association.

Henry George Historical Society. (2009). Henry George.

Retrieved from http://henry

georgehistoricalsociety.org/henry_george

Image of Catalog Cards courtesy of nkuebrich via Flikr

Image of Dashaway hall courtesy of UC Berkeley, Bancroft

Library via Calisphere.

Retrieved from http://content.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/tf7p3009c8/

Image of E.D. Sawyer courtesy of Commercial Printing

House. Retrieved from

http://books.google.com/books/about/History_of_the_Bench_and_Bar_of_Californ.html?id=t-lYAAAAMAAJ

Image of Irving M. Scott courtesy of the New York Public

Library. Retrieved from

http://digitalgallery.nypl.org/nypldigital/id?3937855

Image of the Rudolph Continuous Index courtesy of Greenwood

Publishing Group.

Retrieved from http://books.google.com/books?id=QCddw5cVjVgC

&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false

Images of San

Francisco City, the 1906 earthquake, Library buildings and grounds, Robert

Rea, James Phelan, and the 1930s library staff provided courtesy of the San Francisco

History

Center at the San

Francisco Public Library

Images not credited elsewhere are provided via WikiCommons

Marco, G. (2012). The

American public library handbook. Retrieved from:

http://books.google.com/books?id=_pB43PlC5mAC&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false

Michelson, A. (2013). Kelham, George. Retrieved from https://digital.lib.washington.edu

/architect/architects/294/

Minton, T. (1996, September 5). Card catalog saved – But

S.F. library not sure where to

put it. SF Gate. Retrieved from http://www.sfgate.com/news/article/Card-Catalog-Saved-But-S-F-Library-Not-Sure-2967651.php

New York

Public Library. (2013). Irving M. Scott. Retrieved from http://digitalgallery

.nypl.org/nypldigital/id?3937855

San Francisco.

(n.d.). In Encyclopædia Britannica Online

Academic Edition. Retrieved

from http://www.britannica.com.libaccess.sjlibrary.org/EBchecked/topic/521129/

San-Francisco

San Francisco Board of Supervisors. (1880). San Francisco municipal reports

fiscal year

1879-80, Ending June 30, 1880. Retrieved from http://archive.org/details/sanfran

ciscomuni79sanfrich

San Francisco Board of Supervisors. (1895). San Francisco municipal

reports Fiscal Year

1894-95, Ending June 30, 1895.

Retrieved from http://archive.org/details/sanfranciscomuni45sanfrich

San Francisco

Call. (1906, September 19). Robert J. Tobin, banker, answers the call of

the angel of death. San Francisco Call. Retrieved from http://cdnc.ucr.edu/cdnc/

cgibin/cdnc?a=d&d=SFC19060919.2.98&cl=search&srpos=0&dliv=none&st=1&e=-------en-Logical-20--2878----America+Maru-all---

San Francisco

Public Library. (2013). Wall of Library Heroes. Retrieved from

http://sfpl.org/index.php?pg=2000060401

San Francisco

Public Library. (1900). Book bulletin,

volumes 6-8. Retrieved from

http://books.google.com/books/about/Book_Bulletin.html?id=Sh4zAQAAMAAJ

Shuck, O. (1901). History

of the bench and bar of California: Being biographies of many

remarkable

men, a store of humorous and pathetic recollections. Retrieved from http://books.google.com/books/about/History_of_the_Bench_and_Bar_of_Californ.html?id=t-lYAAAAMAAJ

Vassar, A. & Meyers, S. (2013). John S. Hagar. Retrieved

from http://www.join

california.com/candidate/7505

Wiley, P. (1996). A

free library in this city: the illustrated history of the San Francisco

public

library. San Francisco:

Weldon Owen, Inc.